words

Shopping Carts -- Douglas Coupland

People often say that they're throwing something away, but this statement begs one of the great questions of consumerism, "When you throw something away, what, exactly, do you mean by away? Anyone who has lived in downtown Vancouver knows what "away" means. "Away" means what was once yours, now belongs to a binner, those (mainly) men who roam the alleys with Safeway shopping carts in pursuit of ownerless stuff. Binners are astonishingly fast. You take something you no longer want to own - almost anything, really - and you place it in your back alley. In seven minutes it will be gone, now a part of a capitalist commodity stream almost entirely unscrutinized by society.

Enter Brian Howell

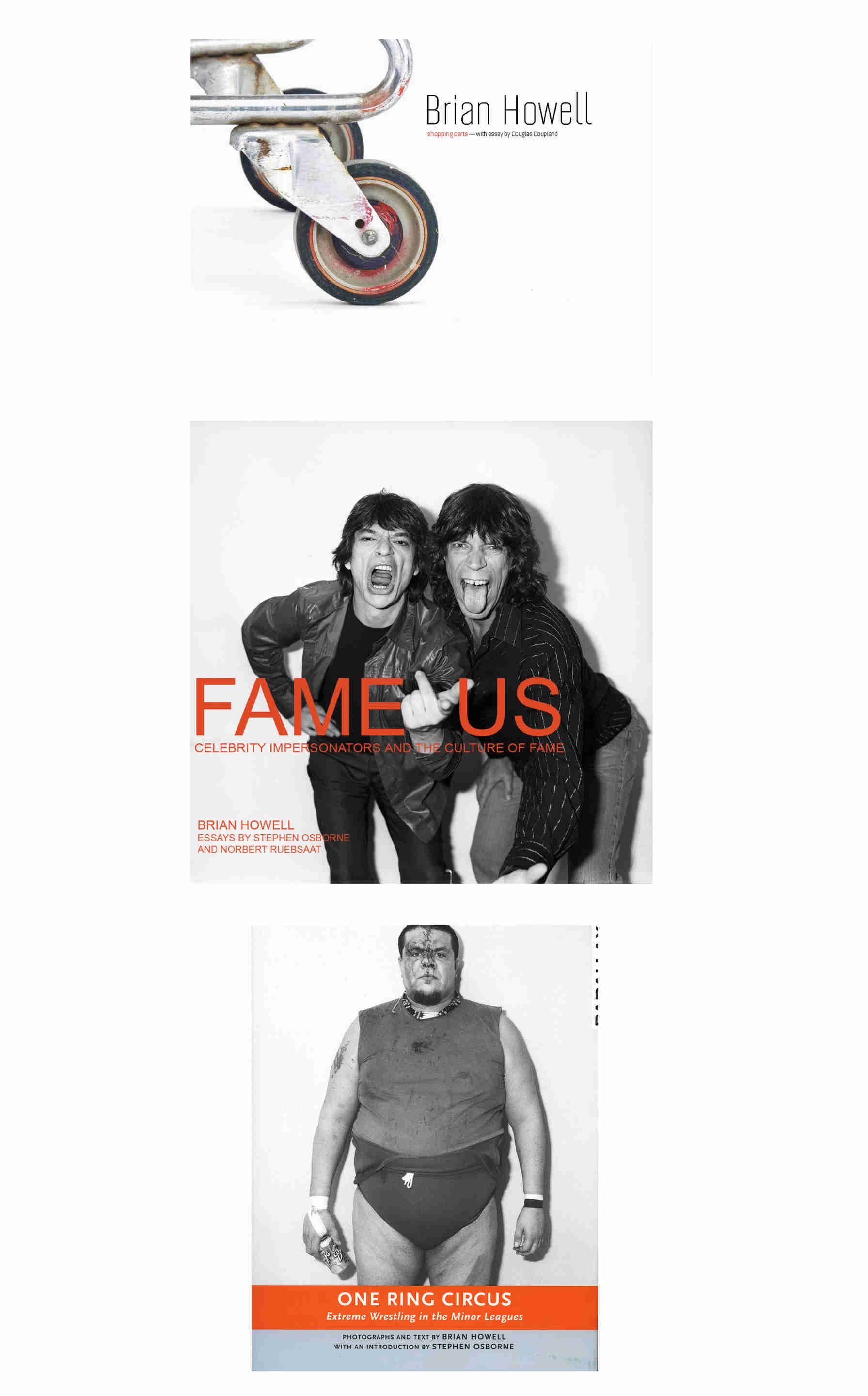

Howell's photographic art practice has evolved over this past decade alongside his professional work as a press photographer. His practice has focused on people inhabiting mainstream culture's fringes, for example, the lower tiers of the pro wrestling circuit, and the world of celebrity impersonators. Howell's recent body of shopping cart work follows that tradition of exploring fringes. He explores society's outsiders while expanding the act into something far broader, into realms that touch on capitalism, green politics, environmentalism, the politics of homelessness as well as the issues of form and materiality.

A good deal of Howell's new body of cart-based work's potency stems from the questions that arise almost instantly upon seeing it. Where did these carts come from? Who owned them?Why those specific things inside the carts? Was somebody's livelihood impacted by its inclusion in the process? Is it decadent to estheticize someone else's eked-out living this way?The answers aren't what one might think.

In undertaking the shopping cart project, Howell was "conscious that the original impetus arose from curiosity about "the other" - from the voyeur impulse endemic to city life".He has also given due consideration to the issues of representation. "In purchasing the carts, I am always transparent about my plans and ask each person to set the price for their cart, then compensate them accordingly. My intention is to photograph the carts and their contents intact, exactly as they were when I bought them. I built a plywood ramp for my old GMC van and rolled in the carts." The carts received no grooming. The white backgrounds are a scientific rather than esthetic call.

Howell also wants it to be clear that none of these objects photographed are the personal belongings of binners -- they are a means to an end, to generate daily cash to keep them going. Says Howell, "I was under the impression that the shopping carts we see on the streets are filled with the personal lives of the people pushing them. " Not true. Binners almost to a one consider themselves capiatlists and valuable to society. Most binners travel tens of miles from the city's core to scrapyards across the city's metro region. The average cheerfully accepted price for a cart was an average of $25 apiece.

Ironically, binners, with their high visibility within Vancouver's civic culture, are often misperceived as evidence of social devolution and its chronic homelessness. Vancouver, among Canada's mildest climates, is the end of the road for those who drift. The city is Canada's largest port which makes it flush with high potency narcotics. Most alleys within a half-mile radius of Main and Hastings will yield untold numbers of needles, bleach kits and discarded cans of Boost and Ensure, someone's meal for the day. Binners, however, don't necessarily identify with Vancouver's homeless situation. They find satisfaction from their work, have a sense of community among themselves, and many are proud of the physical exercise they do. Some have made a point of showing Howell their buff physical condition.

What about the carts themselves? The shopping cart is a powerful signifier of public space, yet also a personal signifier. We've all been at a supermarket and looked into someone else's cart and said to ourselves, "That could never be my cart." Industry meets psyche.

Carts as objects speak of shopping accumulation and capitalism. Howell's carts ask, What is ownership? What does it mean that I 'own' this thing say, a cabbage, and I 'give' it to you - and now you 'own' the cabbage. In one sense capitalism is a magic wand waved over a certain situation that bestows the magic power of ownership on whatever it touches. On the other hand, ownership is an unresolvable tangled, political, environmental, historical, financial mess. But we can say that at the very end of the ownership cycle one finds binners and what they do... and we find shopping carts which were once the cradles of shiny delectable ownership and which have now become the coffins of unwantedness whose presence marks the end of the consumption chain. Binners, in their determination, make one final intervention in that chain, bestow value on what was otherwise slated for a landfill. Cans, bottles, copper wire, and small appliances can easily be turned into cash. But items with no specialized end-use become, in one final burst of entrepreneurship, reenter the retail realm once more.

That pair of jeans hanging over the carts edge -- are those on display, a form of retail? Answer. yes. That wig?That T-shirt? Those vacuum cleaners? Retai, retail and retail. For a society that trains its youngsters by suggesting they operate a lemonade stand while young, the consumer bug never quite leaves. Most people are up for a garage sale, even if it has wheels.

Curiously, Howell's carts and investigations also offer an incidental snapshotof where our culture's technologyis at a certain point in time. For example, binners won't go near a TV set --they're unsellable.Those printers and keypads? Ditto. One has the hunch that binners gave up on typewriters about fifteen years back.

It is also important to view Howell's carts on a formal level, a level where the work's potency stems by it's pure celebration of materuials and materiality. Says Howell, "I've come to see these carts as ready made sculpture that is both visually arresting and filled with meaning. "Important to the carts is Bernd and Hilda Becher's discussion on 'the absence of design' in their work. Also germane to Howell's work are Richard Avedon's portrait of teh American West, as well as William Eggleston ansd his use of everyday objects to reveal calss structure. Both Andreas Gursky and Edward Burtynsky's large scale images of industrial landscapes have sensitized Howell to the globalized and genericzed nature of consumer culture's leftovers. There are only X- number of types of shopping carts out there; like white pplastic bags, they evoke the dark yet bland side of consumption. Empty plastic bottles andbottle caps and denim are the same the world over. The cart images are depressingly and poignantly global.

As an artist, Howell's Shopping Cart projectmarks a shift in his development, moving him firmly into a conceptual approach, while he simultaneously explores the possibilities of working with found objects. "Since buying that first cart, I have been considering artistic strategies for representing these meaning-laden objects and in this I have been conscious of wanting to shift the focus away from the conditions in which the carts are created and look

instead at the carts themselves. These carts are not something most of us experience at close range, but we are all curious an our eyes are drawn to them. This series permits me(and through my camera, theviewer) the pleasure of simply looking at thecarts and their contents." The intent of this projects is to allow the carts to speak for themselves.

Howell has found the most effective approach to remove the cart from the street andphotograph them against a white backdropusing atechnique that allows for th highest possible image resolution. "For the first time, I'm taking found subjects matter out of context and shooting it in the studio, in a controlled situation, slowing down to meditate on each new piece. The project employs recent technology yto stitch together large prints that render extreme detail in a manner not previously possible with film. In terms of technique, the project is pushing me to apply my skills in an unfamiliar manner."

Howell hopes the project will contribute to the ongoing development of photography as an art form. He like that "it responds to the world aroundus and reflects it back in ways that elicit emotion and provoke thought. It is one of the functions of photography to hold the world still for a momentso that the viewer can consider it anew. High-resolution images rendered as large prints offer the opportunity to consider the carts and their contents in fine detail. Isolated in this mnner, the carts pose deep questions about our daily lives."

Indeed, to survey Howell's carts, one can't help but wonder about the pace and sustainability of our current culture, an the arbitrary an fluctuating nature of value.And by speaking of the end of acertain mode of existence, they force us to weigh human historyversus geological history, and, ultimately, our mortality.

Impersonators - Barry Dumka

By one estimate there are 85,000 Elvis impersonators around the world. In our starstruck age, celebrity impersonators are aboom industry. Part of that growth is explained by the dominant social and economic power that a celebrity commands yet can't always take advantage of in person. Like th bones of saints in the Middle Ages, there are still not enough celebrities to go around. So there is now a big markey for mimicry, for subjugating self-distinction to serve as celebrity avatars. Alice doesn't live here anymore - an even cheaper version of Paris Hilton does.

For his Impersonator series of portraits, Brian Howell has used an old motif - paparazzi snapshots - to place front andcenter the diminishing value of individualityin a culture drugged by fame. For Howell himself, this series is transitional as it shifted his work to a more conceptual stage. The project was developed in an early part of his career when Robert Frank andth street photographers of the 1970's still held sway. Certainly th influence of Diane Arbus is witnessed in the way Howell smudges the light and it is convenient to see these impersonators as among her eccentrics.

But in this series Howell presents a new type of person - an eager participant in the hollowing out of society's appreciation for authenticity. They are ciphers for a soulless time or cultural market where theonly stock going up is the value of fame. Howell's titles tell the riddle of these split personalities. pavel as Bono. Chris as Madonna, Jerry as Saddam. Thefirst part might as well read blank as we brighten only with mention of the celebrity's name. That is who we see first. it is a clever visual conceit by Howell to makethe viewer part of this particular fame game. Do we care enough to see who is behind the mask; does theindividual care enough to be seen Everyone seems very comfortable adopting thepose and purpose of someone they are not.

Howell's photographs - brilliantly captured in a flash of silver light - are compelling, even chilling. These are people who want to be famous more than they want to be themselves..